First, let us be very clear about something: this is not a book review. I am neither qualified nor inclined to perform any kind of deep analysis of literary texts. There are scholars who are far better trained for that task than I. You can think of this blog as more of a personal reaction than a critique. I am merely sharing my thoughts on books that I like which have made an impression on me.

My first target is Austerlitz by the German author, W.G. Sebald. This novel was published in 2001, but I have only recently discovered Sebald. Although my tastes are not often contemporary, I do seek out books that are unusual and are dense enough to envelop me and draw me deeply into a state of imaginative contemplation. Austerlitz is such a book. This remarkable text is really an extended, thirty-year conversation between the narrator and Jacques Austerlitz, a man who, as a child, survived the trauma of the Second World War but has almost completely blocked out his memories of that time. Shipped on a Kindertransport from Prague to England as an infant, Austerliltz is soon adopted by a Welsh preacher and his wife, and the early part of the novel describes the grim, emotionless relationship with his foster parents. His foster parents die while he is still in school, and it is at this point that Austerlitz begins to learn something of his origins. He eventually studies to become an academic, specializing in European architectural history, and it is within this motif that the novel develops much of its richness. There are long passages describing crumbling forts, train stations, concentration camps, and other edifices that evoke a sense of lost history and faded memories. It is these melancholy landscapes that reflect Austerlitz’s own sense of dislocation and amnesia regarding his past. He is rootless in a world where the past ceases to have any meaning. Even the ultra-modern National Library of France, a vast repository of knowledge, offers no hope to Austerlitz. Consider the following description of the overly structured nature of the library:

The new library building, which in both its entire layout and its near-ludicrous internal regulation seeks to exclude the reader as a potential enemy, might be described…as the official manifestation of the increasingly importunate urge to break with everything which still has some living connection to the past.

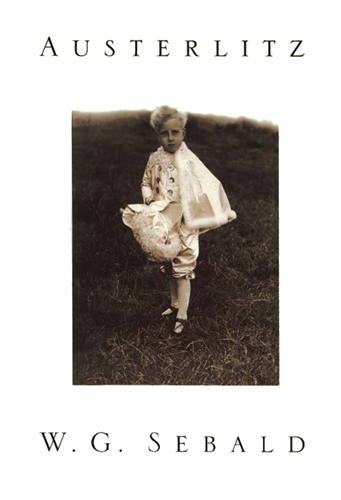

This section also provides an example of another appeal of this novel: its wonderfully dense sentence structures. Jacques Austerlitz speaks as an academic, and there is richness in his long, descriptive sentences. At one extreme point, a single sentence continues for six and a half pages. Sebald also follows the practice not using paragraph breaks. This technique is effective at conveying the persistent desperation Austerlitz feels as he tries to find answers about his past, but it is, at times, awkward to read. Fortunately, Sebald does periodically break up the text with a selection of unusual images. The black and white photographs of lonely buildings, maps, and drawings give the work a documentary feel while reinforcing Austerlitz’s, and more generally post-war Europe’s, sense of a disconnection from history.

History’s faltering hold on modern imagination is one of Sebald’s key motifs. Austerlitz’s own troubled history is hinted at by triggers in the external landscape that, at times, ignite flashes of memory. Austerlitz, though, is unable to fully comprehend their meaning. Sebald’s metaphors beautifully integrate these two concepts, as seen in one of Austerlitz’s descriptions of Prague:

Then I sat on a bench in the sun until nearly midday, looking out over the buildings of the Lesser Quarter and river Vlatava at the panorama of the city, which seemed to be veined with the curving cracks and rifts of past time, like the varnish on a painting.

This book is not easy reading, but it is engrossing. My personal fascinations with architecture and the literary technique of using the external world to represent the internal state of the characters are what first attracted me to this novel. Sebald’s skillful exploration of the loss of history and memory, on both the personal and collective scale, only added to my enjoyment of this story. This is not a happy novel, but it is a deeply satisfying contemplation of the dark spaces created by traumatic events.